Customer reviews on the internet

Online reviews mean more transparency for interested parties and ideally a clue about real value or quality in a sea of advertising. However, the power of few stars awarded can also mean ruin for companies. It is not surprising that the immense importance of user testimonials and the average value of stars awarded tempts many a company into trickery. Customer opinions and advertising are becoming increasingly blurred.

According to Scamadviser, 39% of all counterfeit products ordered online are purchased from website shops and 29% from online marketplaces such as Amazon, Ebay or Alibaba. Embellished star ratings on both web presences deliberately mislead customers. Last year, e-commerce software specialist Capterra conducted a representative end-customer survey, the results of which suggest that more than half of online shoppers assume customer ratings are fake. As a result, online shoppers look at an average of five to 20 reviews before placing an order. The majority (39%) find online reviews more important than recommendations from friends and acquaintances (23%). Similarly, many shoppers prefer a not-so-good average rating to a better average rating if the less good one is derived from a much larger number of ratings.

Whereas about a decade and a half ago user ratings were only displayed by the large providers Ebay (reliability of a seller) and then Amazon (product quality), these market leaders soon expanded customer feedback to include shipping time, product quality, customer communication, support, etc. To create trust in online products and sellers, almost every small business, tourist attraction and public service is now linked to publicly accessible user ratings, if not on its own website or on Facebook fan pages it has set up itself, then at least on platforms specialised for this purpose. The resulting rating industry is complemented by Google automatically creating a separate page with information on location, opening hours, etc. for organisations and companies, without their intervention, where customer experience reports are also displayed.

Big names in the review business are Trustpilot (2021: over 2 million new reviews per month) or trusted shops in retail and service providers (2019: over 20 million registered customers) or TripAdvisor in travel (2020: a total of 884 million reviews).

Hardly anyone books a holiday trip today without first looking at the reviews of their destination on the internet. You can find a rating for almost anything, be it a doctor (docfinder), a beach (beach-inspector) or a film (imdb) that was in the cinemas 40 years ago, for example.

There are specialised portals for almost everything that allow employers (glassdoor or kununu) or, for example, school teachers (Lernsieg) to be rated. The CoV pandemic has generally further fuelled online commerce and thus interest in customer ratings.

Open or closed rating system?

The omnipresent rating trend was originally triggered by e-commerce providers themselves. In the past, they only asked for a simple product rating in their own webshop after the purchase. This method is called an integrated rating system. Smaller companies usually did not have their own rating system, but did not want to do without the advertising effect of customer opinions in the competition with the increasingly dominant marketplaces such as Ebay or Amazon. Specialised companies soon established themselves that rent out trustmarks to webshops and thus provide corporate customers with a graphic badge with a current average rating for their homepage. This is intended to prove the reliability of the company to potential customers. These trustmarks are usually based on customer feedback from verified purchases, i.e. only if the customers have actually bought from the evaluating provider.

These trustmarks offer customers the advantage over home-grown rating systems of sellers that they are not subject to the immanent sales interests of a single company. After their consumption or delivery of the goods, customers are actively asked by the rating portal on behalf of the retailer about the purchase experience. And this for several reasons:

- Firstly, to reach a relevant amount of feedback entries faster.

- The second reason for the payment of active contact by the trustmark provider is to collect not only negative evaluations in the case of problematic orders. This is because people tend to give feedback only when things go wrong and hardly ever when everything has gone well.

- Thirdly, retailers want to remind customers of a good buying experience by actively addressing them. On average, around 80% of all reviews are positive.

In German-speaking countries, the monthly costs for a company entry on such a seal of approval platform range from 10 to about 250 euros. With the largest providers, the monthly rent for the seal has settled at around 100 euros; entrepreneurs can pay for additional functionalities. With this type of seal of approval, or even if the system is integrated directly into the ordering process and is based on internal customer feedback (e.g. at Amazon), one speaks of so-called closed platforms. Here, only customers invited by email can submit a rating. However, this carries the risk that a distorted picture of the reputation of the company or product can emerge and the question of how the result came about is often not particularly transparent. Especially not if there are only a few ratings or if a rating system is new.

It also has a distorting effect when online retailers make a tribe of selected customers into regular product testers and bind them to themselves through benefits, by sending them new products earlier or free of charge or giving them vouchers. Participants in such regular product tests then act similar to influencers and usually their reviews are more positive than the unadorned average. Many traders are absolutely dependent on the presence in marketplaces and submit to this scheme of gifts to testers for reasons of market logic. The other disadvantage of closed platforms is that unregistered consumers cannot find the reviews of the trader as easily as on open review platforms(e.g. Trustpilot or Scamadviser), where in principle everyone can review any company without restrictions.

Rules in e-commerce and media law

According to § 6 para. 1 of the E-Commerce Act, review platforms are obliged to label sponsored products or profiles. Thus, paid reviews - which in principle are nothing more than advertising - must also be clearly marked as such on the rating platforms. The Media Act also stipulates in §26 that websites must make purchased reviews clearly recognisable as advertising. For this purpose, words such as "Paid advert", "Advertisement", "Sponsored by" or similar are usually placed near or on the paid ad or the sponsored profile.

If domestic influencers are unsure whether they have to declare a post as advertising or not, or whether they even count as an influencer, the Austrian Ethics Council for Public Relations has launched a low-threshold website that helps to understand the set of rules through simple entries. The guide at https://influencercheck.at/ provides clear instructions for action by answering simple questions.

Reviews on social media and the viral effect

Fan pages of companies on social networks such as Facebook offer the possibility for customer comments or even quantitative ratings (points or star ratings, red - green coloured bars). In general, social networks and open platforms catalyse the impact of customer reviews on business, both good and bad. However, the easier it is to create new fake profiles on the social network in question and the smaller the number of users, the more questionable these ratings are. As a counterpoint, however, there are also social media groups, bloggers or passionate fake site hunters who specialise in collecting misleading praise and fake shops.

Worth mentioning is the Facebook group “Scam Alert Global” with 15,000 members and the "Fake Shop Buster" James Greening, who lists entire fake networks. These networks, mostly from China, create numerous Facebook and web shop pages to sell non-existent products. Of course, fake customer reviews are added accordingly for this. In several cases, over 200 (!) professionally designed shopping pages with different names were created for the same "company" in the background, which victims repeatedly accuse of fraudulent practices.

If one is not careful, it is often difficult to tell whether it is a conventional webshop, dropshipping (goods arrive from the Far East at some point without support in case of problems) or even advance fee fraud (paid order will not come). In the collected examples, there may also be hybrids of all three "business models". In large networks such as Facebook, the comment function can trigger a feedback response to negative reports, which encourages more and more users to express similar opinions.

Such a "shitstorm" of negative Facebook user comments is particularly distressing for companies whose customer base was built up through viral marketing campaigns. Since a company's Facebook page is usually also displayed high up in Google's search results along with the average rating there, a wave of indignation with corresponding "dislikes" also has an impact on the purchasing decisions of potential customers who do not use the social network at all.

A clumsy attempt can be seen as a freely invented seal of approval by some traders who, for image reasons, want to give the impression of an external inspection. However, this has never taken place; the supposed seal is nothing more than a mere advertising graphic with no content, a decoration intended to convey the appearance of proof.

For an open rating portal, its own credibility is the basic prerequisite of its business model, so it should be assumed that the results are not manipulated in the interests of its corporate clients or their competitors. However, there are also black sheep who commercially exploit the inability of open platforms to easily verify the claims.

Purchased Fake Reviews

Agencies specialising in fake customer testimonials offer such positive reviews for sales or open review platforms at a unit price. So-called clickworkers are hired by such agencies for a few hundred euros and write 5-star fake reviews serially and on commission. The backers evade justice in tax havens and opaque corporate networks. The article in the magazine Extrablatt (from page 106) explains the argumentation of the sinister rating merchants; companies should not have a bad conscience when buying fake ratings. A rating seller sets out his logic on his website with the text "Why is it morally correct to buy ratings?" as follows: The person who does not cheat has only himself to blame, because he puts his company at an economic disadvantage against the competition, since the latter certainly uses the practice as well. In this way, the abuse of the review circus, which is susceptible to falsification and is thus becoming more and more absurd, is presented by such review traders as essential for the survival of companies.

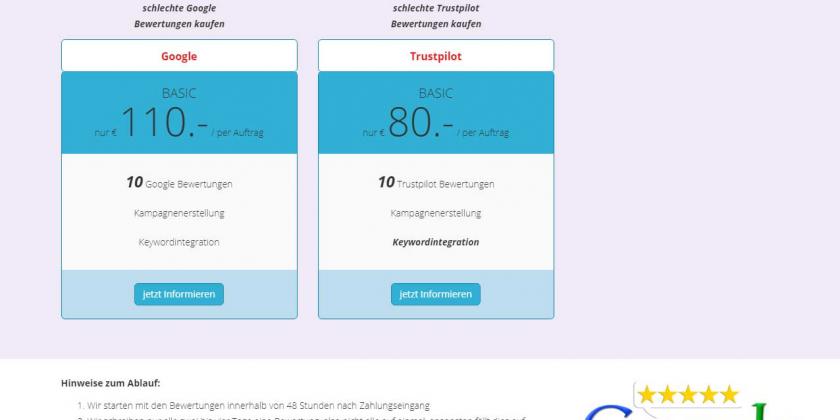

Some agencies operate particularly brazenly with package offers for fake negative reviews about the competition. At reviews-buy.com, for example, the special offer is 110 euros for 10 negative Google reviews about a competitor or 80 euros for the same at Trustpilot. Buying such a "service package" is supposed to make one's own shop look better in comparison. The assessment of media law expert Prof.Dr. Zanger in the Extradienst interview is also interesting. "Basically, buying reviews is namely not punishable." Zanger does later qualify that gross untruths about the competition in such reviews are to be interpreted under criminal law, but in practice alleged untruths about the competition are more likely to lead to injunctions with subsequent correction than to penalties. On the subject of fake customer reviews, ARD broadcast the recommendable report "Faules Lob im Netz" (Fake praise on the net) with background knowledge from a whistleblower.

Entrepreneurs respond to criticism and to fakes

If competitors blacken a competitor through fake entries, this is unfair competition and can be reported if it is possible to find out who is behind it, despite all the difficulties. In the case of unjustified customer reviews, companies have the option of having these deleted from their company profile on a review platform if they can objectively refute the alleged accusations with facts. Frequently, however, a counter-statement is added by the company in the case of conciliation. The deletion of a critical customer review is possible, but it harms the review platform and is normally avoided.

This is especially important on open platforms, where the purchase of the good or service by the reviewer is not a prerequisite and is not usually checked.

Interestingly, studies show that customers find local companies more credible if they have, for example, four and a half stars than a full 5-star rating. Errors are tolerated by customers in moderation. When companies admit mistakes, make efforts to resolve them, and make this clear in the public response to the bad customer review, the effect of an original negative review is reversed, and actually enhances the company's image.

Echte Kundenbewertungen - dennoch gefiltert und erschlichen

Ganz unverblümt versenden vor allem Marketplace Händler:innen (etwa auf Amazon) Aufforderungen zu geschönten Bewertungen mit der Versandware aus. Darin bieten manche einen Rabatt Code auf die nächste Bestellung, sofern die vollen 5 Sterne vergeben werden. Die andere Masche ist es, zwar vermutlich echte, davon aber nur die gut ausgefallenen Kundenbewertungen in Webshops anzuzeigen, die etwa auf der Drop Shipping Plattform Shopify laufen. Loox ist eine solche Firma, die mit Customer Reviews Handel treibt und hoch unseriös zu sein scheint. Negative Reviews werden nicht gezeigt, tendenziell positiv abgegebene "moderiert". Somit wird der Gesamteindruck eines Produktes komplett in die gewünschte Richtung gebracht. Für Webseitenbesucher:innen ist der Unterschied zu Fake Bewertungen somit unwesentlich. Das Produkt erscheint als einwandfrei bewertet, obwohl es das nicht ist.

Metadata and AI in the fight against fakes

Meanwhile, many rating portals are networked. This is called rating aggregation and means that ratings from different platforms are shared and flow into a common overall result. Google also displays aggregated rating results from licensed rating partners directly in the hit list of the search engine itself, if a company rated by the partner has placed an ad on Google in order to be ranked at the top of the search hits. If a Google page with additional information such as address, Google Maps entry and opening hours is available for the search result, only Google-internal so-called "Google reviews" are displayed there.

Neutral rating platforms such as Scamadviser specialise in combining reviews and ratings from third-party portals (e.g. Trustpilot) as well as fraud warnings from their own users and their own fakesite hunters, as well as IP address queries (whoIs) to owners directly on the portal in a meta result. The algorithm then calculates the partial results according to its evaluation key as an overall result. Scamadviser cooperates with some European Consumer Centres in reporting scam sites.

The analysis portal Fakespot now considers 42% of all Amazon reviews to be fakes. This means that the figure for 2021 has risen sharply compared to the 36% of the previous year. The algorithm of Fakespot evaluates customer reviews on online marketplaces such as Amazon, Shopify, Ebay, Walmart, BestBuy etc. after installation as a browser plugin or as an app in the smartphone and an artificial intelligence filters out the fake reviews and blocks their display as well as the display of fake goods (counterfeit) on the device of users of this popular app.

Naturally, Amazon is not very fond of this start-up and only had the app removed from the Apple Store in July 2021. Apple's usage rule 5.2.2 prohibits monetised apps from accessing the content of others without their consent. Since Fakespot has designed its app to technically overlay itself on top of the Amazon website and be displayed as a layover, this rule has not been followed. However, anyone who wants to use Fakespot can still do so in the browser of an Android smartphone or as a browser extension on a computer.

A competing product to Fakespot is ReviewMeta. In a similar process, and also available as an app or browser extension, ReviewMeta only allows customer reviews rated as genuine to be fully included in the recalculation of the overall result from customer reviews; reviews classified as less credible by the AI are mathematically only included proportionally in the meta result. The adjusted final result presents itself to customers as a rather useful orientation aid with average ratings corrected downwards.

Links

Guide for Influencers of the Austrian PR Ethics Council (DE)

https://influencercheck.at/

Mimimaka article on fake ratings (DE)

https://www.mimikama.at/aktuelles/mehrere-quellen-entlarven-fake-bewertungen/

Interview on the topic with ECC Director Dr Herrmann in Extradienst from page 106 onwards (DE)

https://www.extradienst.at/ed-3-4-21/

BR (Bavarian Broadcasting Company) radio programme on customer reviews (DE)

https://www.br.de/radio/bayern2/klicks-mit-konsequenzen-die-vor-und-nachteile-von-online-bewertungen100.html

Austrian Quality Mark for E-Commerce (WKÖ)

https://www.guetezeichen.at/

Ombudsman's Office Internet Article on Fake Ratings on Online Platforms (DE)

https://www.ombudsstelle.at/faq/online-bewertungen/wie-erkenne-ich-werbung-auf-einer-bewertungsplattform/

Website of "fake site hunter" James Greening publishes alerts

https://fakewebsitebuster.com/